Addressing the GDPR issue - Patterns and Antipatterns for success

Published:

Content Copyright © 2017 Bloor. All Rights Reserved.

Also posted on: The Norfolk Punt

As I observe the emerging “GDPR Industry” I am often reminded of the more dysfunctional aspects of the “Y2K Industry” around 2000. Nevertheless, both GDPR and Y2K are/were real issues and in the same way that some firms gained real business benefit from their approach to the Y2K issue to justify the cost (by taking the opportunity to refactor or triage badly written systems and to introduce asset management, for example), some (more mature) firms will gain business benefit from GDPR. However, for some firms both issues are are just costs, and such firms spend money on such issues without getting positive business benefits from the spend – and without even managing the associated risks very effectively.

At this point, it is probably necessary to point out that a lot of work and money went into “fixing Y2k” and assessing risk from the certainty of hindsight is often misleading. There were real Y2k failures – at that time my company accounts ran on a PC accounting package, which was written well into the 1990s, and which irretrievably corrupted all its accounts data at the start of the financial year before Y2K (i.e., as soon as a date past 2000 was added, well before 2000 itself).

As this is implying, GDPR is just one instance a generic type of issue (one with a scope that crosses all areas of a company’s business, with both business and deeply technical implications, and with an externally-imposed, non-negotiable deadline). There are known good-practice patterns associated with addressing such issues, firmly grounded in experience, which can help us to address them. More frequently met in practice, however, are known antipatterns, which will lead to disaster – or, at least, waste money (IT, in particular, has made reinventing the wheel into a “best practice”; but it sometimes seems even more keen on reinventing square wheels).

What sort of antipattern am I talking about? Well, the most obvious one is the “silver bullet”: I pay lots of money to a technology vendor, and hope that the problem will just go away, without me having to train anyone, change my culture or, in fact, worry about anything much. This is quite similar to the sale of indulgences in medieval Europe and about as effective – it’s pure cost, and does little to affect risk (but you might get lucky). There was plenty of snake-oil sold to address Y2K, there’ll be plenty more sold to address GDPR.

Another antipattern is “not my problem” as in “Y2k is a mainframe problem, it won’t affect PCs”. Its current incarnation is around statements like “Brexit means that GDPR no longer applies” (not true, and not just because GDPR comes into EU law in 2018, before we will have left the EU); or “we don’t trade with the EU” (GDPR applies to EU citizens, even if they live in the UK and come into your shop in London).

Bloor has created a GDPR practice centred on delivering business benefit from GDPR. We will base our approach on the use of experience-based “good practice” GDPR patterns and, probably more usefully (since few of us work in high-maturity, highly effective organisations, no matter what Marketing says), on recognising emerging antipatterns in time to do something about them.

This blog is not the place for a detailed analysis of GDPR patterns/antipatterns. I’ll just document a couple in detail to give an idea of how this idea could be developed more formally:

Pattern name and classification: GDPR Institutionalisation – GDPR strategy

Intent: This pattern describes an efficient top-management approach to addressing GDPR effectively and is an essential basis for achieving business benefit.

Also known as: Senior management buy-in.

Motivation (forces): GDPR is brought to the attention of the Board, possibly by a lower-level “GDPR champion”.

Applicability: This pattern is used whenever an organisation needs to address GDPR; that is, whenever it stores or processes PID for data subjects who are EU nationals, whether or not they live in the EU or whether or not the associated transactions took place in the EU.

Participants: All of the people in an organisation. Plus partners, customers.

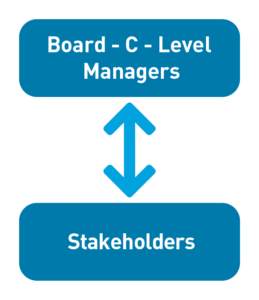

Collaboration: A GDPR taskforce, with representation at all levels (including Board level) will coordinate the GDPR effort.

Consequences: The process and cultural requirements of GDPR are addressed, with buy-in at all levels, and the organisation is, thus, free to pursue business benefit from GDPR, knowing that any risk is being managed. However [trade off], considerable Board resources and strong management will be necessary.

Implementation: In summary/overview, the board will set up a GDPR taskforce, with a direct reporting line to the Board, which will decide whether or not to appoint a DPO (Data Protection Officer) and designate GDPR responsibilities. The GDPR Taskforce will oversee a full compliance program including Personal Information Audits, Information Asset Management, HR reviews and training/induction programs.

Sample process: This will remain a manual process.

Known uses: TBA – once Bloor identifies suitable (possibly anonymised) case studies.

Related patterns: All GDPR patterns have some relationship to this one, as none will work well, in practice, without top management buy-in.

Matching antipatterns: Several, including “Throw it to the techies“, “Abdicate to consultants” etc.’ Perhaps the most worrying antipatterns to avoid are “GDPR board micromanagement“, often associated with “GDPR Command and Control diktat“. GDPR management is, fundamentally a cultural and privacy issue – top management involvement is necessary but not sufficient, and it will need informed buy-in at all levels of the organisation. It is not going to be something that board members can manage and control by themselves, nor something for which you can say to an organisation “just do it – or else”.

Antipattern name and classification: Silver bullet – GDPR strategy

Intent: To abdicate responsibility for GDPR by paying a vendor for a simplistic “GDPR Solution”, hoping that any blame for GDPR failures can be diverted from the managers responsible.

Also known as: “Buying the best of breed vendor GDPR solution“

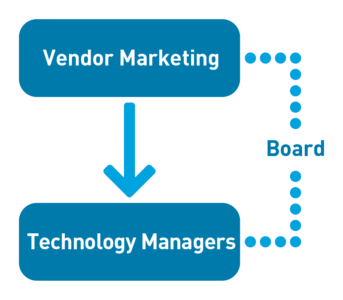

Motivation (forces): Normally, this approach is sold to an organisation by vendor (or consultancy) marketing.

Applicability: Typically, immature companies operating with internal silos.

Participants: Mid-level managers, often in technology departments.

Collaboration: F2F, or silo’d email etc.

Consequences: The “silver bullet”, even if successful in one area (which is not a given) only addresses part of the GDPR issue, leaves significant risks unaddressed or unrecognised, and is purely a cost to the organisation. This antipattern is recognised by lack of senior management interest in GDPR; lack of anyone taking responsibility for GDPR itself (instead of the implementation of the GDPR technology); poor knowledge of the content of the regulation; and a poor match between organisational goals and the requirements of the GDPR regulation.

Re-routing: Implement the GDPR Institutionalisation pattern; set up a GDPR taskforce with representatives at all levels and across all departments; provide GDPR training; consider employing an experienced GDPR mentor. The technology you are buying may, or may not be useful; put it on hold until you know how you want to manage personally identifiable data at the strategic level so as to avoid heading off down a rathole which distracts you from bigger issues

Sample code: This is a manual antipattern.

Disaster movie scenarios: TBA – once Bloor identifies suitable (anonymised) case studies.

Related antipatterns: The silver bullet is a technology-focused distraction from gaining value from addressing the issue as a whole but similar distractions can arise internally with the “Throw it to the techies” antipattern; or from external consultants without specific technology to sell you – the “Abdicate to the consultants” antipattern.

Matching pattern: GDPR Institutionalisation.

The sort of business benefits that can be expected from a mature approach to the GDPR issue, with full top-management buy-in, include:

- Increased TRUST between an organisation and its customers, leading to less “churn” and a greater willingness to provide personal information – which can be used for income-generating “know your customer” initiatives;

- Increasing market-share, at the expense of companies not GDPR-aware;

- Fewer barriers to strategic mergers and partnerships, which, presumably, have beneficial business cases;

- Better managed risk, reducing barriers to business innovation (more freedom of action, to exploit Personally Identifiable Information for the good of the business);

- Better conversations with the GDPR regulators, reducing any associated risk, mitigating any fines and wasting less time on compliance efforts.

Frankly, any manager that isn’t viewing GDPR with the aim of getting business benefit from the effort involved, is becoming a danger to his/her company and employees. A good guide to what is involved with GDPR comes from Bird and Bird – it is probably more of a legal and cultural issue than a technology one, although it is, in fact, all of these – and more.